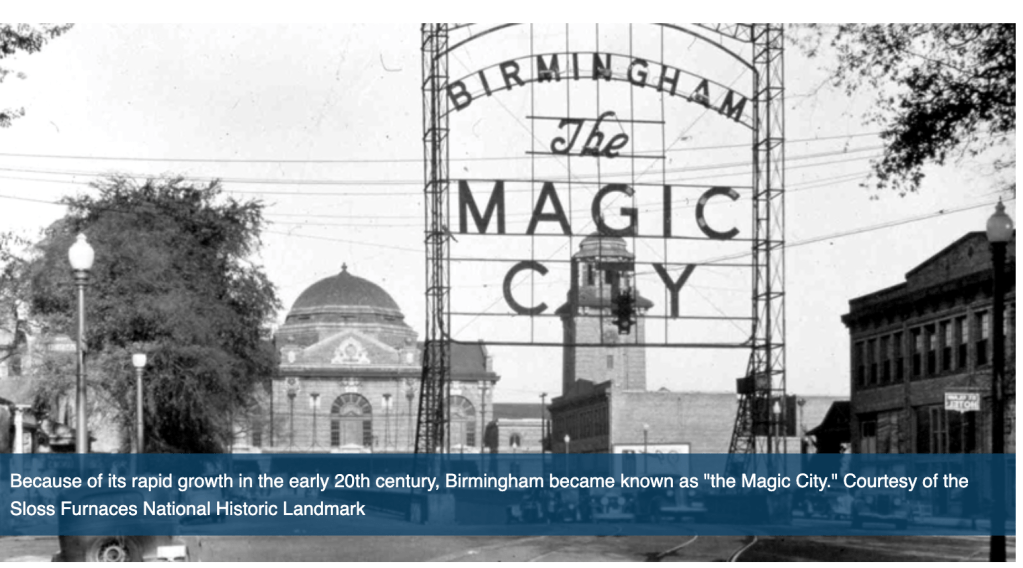

Birmingham, Alabama, founded in 1871 during the post civil war reconstruction period, was called the “magic city” because of its fast pace of growth during the period from 1881 through 1920. The city’s population expanded from 3,000 in 1880 to 260,000 by 1930. Birmingham was built at the crossing of Alabama & Chattanooga and South & North Alabama railroads. It had nearby deposits of iron ore, coal, and limestone – the three main raw materials used in making steel and iron. Birmingham is the only place in the world where these minerals can be found in significant quantities and in close proximity, so Birmingham was planned from the start as a steel and iron producing industrial city. (Wikipedia).

It also had a competitive advantage over northern industrial cities: cheap labor. The availability of a large population of destitute freedmen and impoverished whites in the vicinity of the coalfields offered mine owners an important advantage: workers who were both desperate enough to settle for meager wages and so thoroughly divided along racial lines that they would not organize to protest their predicament or so those in power thought. They did not anticipate the formation of one of the South’s few viable interracial labor unions, District 20 of the United Mine Workers. In 1908, they went on strike for two months, but the strike was crushed by the mine owners when they convinced Alabama Governor Comer to send in the Alabama National Guard.

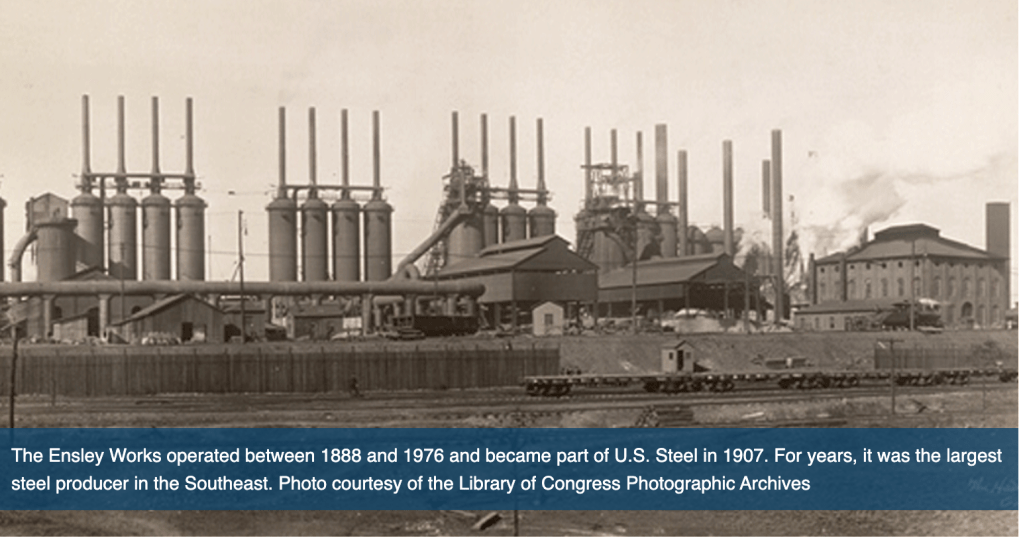

A nationwide depression in the 1890s caused mining and furnace companies inAlabama to fail. Sloss and Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad (TCI) purchased some of these firms and greatly expanded their operations. Sloss reorganized as the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company in 1899 and became the second-largest iron manufacturer in the state. Later, outside investors from New York gained control of Sloss and TCI, and Pioneer was absorbed by Ohio-based Republic Iron and Steel Company, leaving Woodward as the only locally owned ironmaking firm. (https://encyclopediaofalabama.org)

The Great Depression that began in 1929 devastated Birmingham’s economy. Production of steel and pig iron shrank to the lowest levels since 1896, and operations at TCI, Republic, Sloss-Sheffield, and Woodward were drastically curtailed. Business leaders fought bitterly against labor reforms enacted under the New Deal, particularly the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which aimed to raise the wages of southern laborers to the level of their northern counterparts. Labor unions won recognition against strong resistance, but unemployment reached unprecedented levels.(https://encyclopediaofalabama.org)

Industrialists soon realized that Alabama’s coal reserves, which remained plentiful, commanded higher prices in foreign markets than coke-fired pig iron, which was becoming uneconomical to produce. In 1970, USP&F’s last active furnace in Birmingham, one of the two that had been remodeled on the site of the original Sloss Furnace Company, shut down for good. In 1980, Jim Walter Corporation closed the huge new furnace that USP&F had erected in North Birmingham in 1956, then dismantled and sold it for scrap. Even Woodward, long the most profitable company in the Birmingham District, was forced out of business in the early 1970s, and only U.S. Steel’s Fairfield plant remained in production.

From its highest population of 340,887 in 1960, the population was down to 200,733 in 2020, a loss of about 41 percent. White flight to the suburbs after the city was integrated in the late 1960’s contributed to the population decline. Today most of the metropolitan area lies outside the city itself. Other businesses and industries such as banking, telecommunications, transportation, electrical power transmission, medical care, college education, and insurance have diversified the Birmingham economy. Mining in the Birmingham area is no longer a major industry with the exception of coal mining.