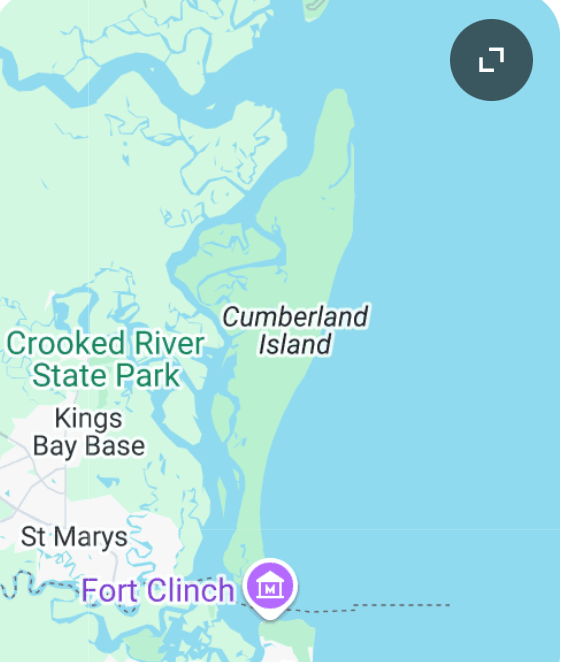

The first inhabitants of Cumberland Island were indigenous people who settled there as early as 4,000 years ago. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Timucua people lived there and interacted with the Spanish missionaries. Like most indigenous people at the time, their numbers were decimated by diseases brought by the Europeans. The Timucua eventually relocated to an area near St. Augustine, Florida. The English general James Oglethorpe arrived at the Georgia coast in 1733. In 1735 he made a treaty with the Creek nation, and claimed ownership of the coastal islands between the Savannah River and St. Johns River for the British.

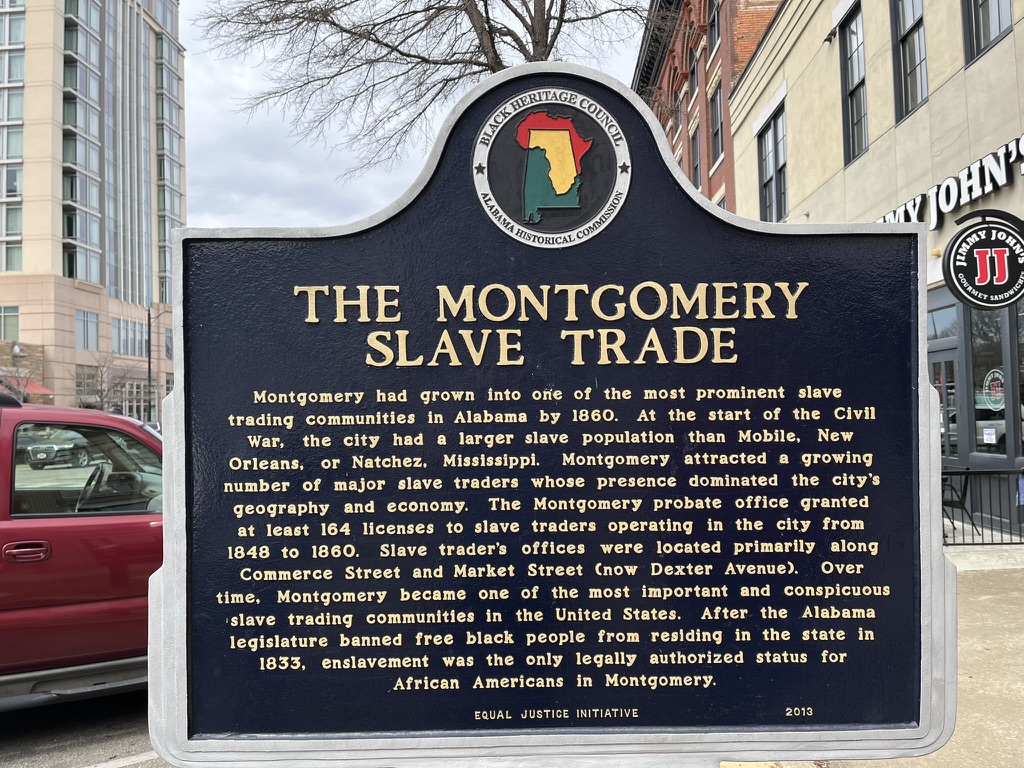

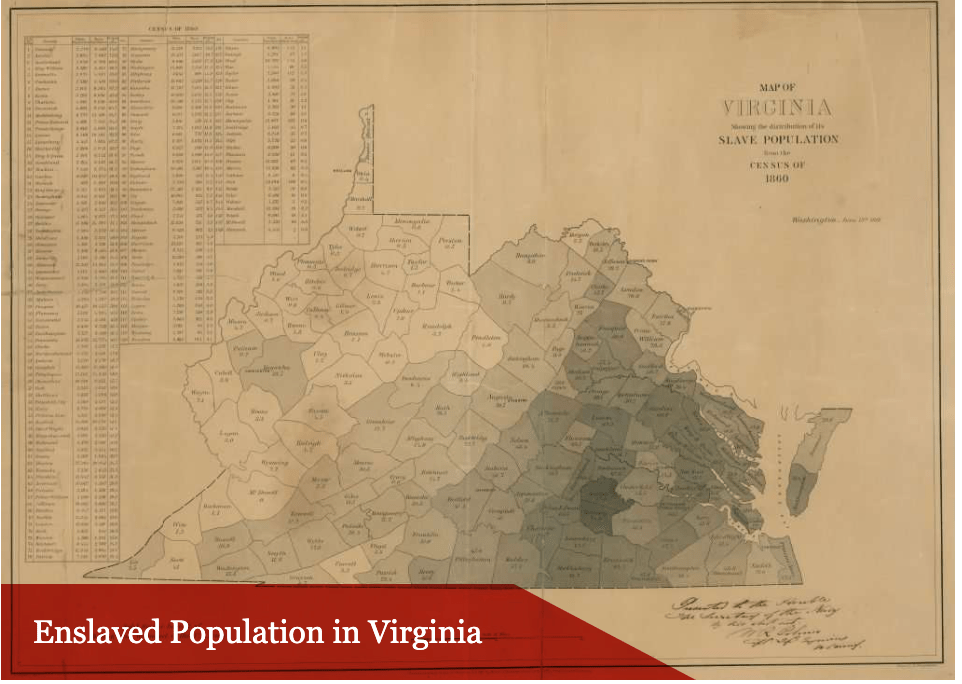

According to the National Park Service, slavery in Georgia became legal in 1751, and the early European settlers on Cumberland Island enslaved Africans and African Americans to grow rice, indigo, and Sea Island cotton.

As the demand for enslaved African labor with rice-growing expertise increased from 1800-1865, over 13,000 Africans were enslaved and brought from the “Rice Coast” and ”Grain Coast” (Senegal to the Ivory Coast) African regions, bringing their sophisticated knowledge of rice and grain harvesting. This invaluable knowledge of rice cultivation under challenging conditions contributed to coastal Georgia becoming one of the major rice-producing areas of the period and greatly influenced the region’s demographic makeup. In fact, by 1860, over 500 enslaved people lived on Cumberland Island, outnumbering white inhabitants by a ratio of seven to one.(visitkingsland.com)

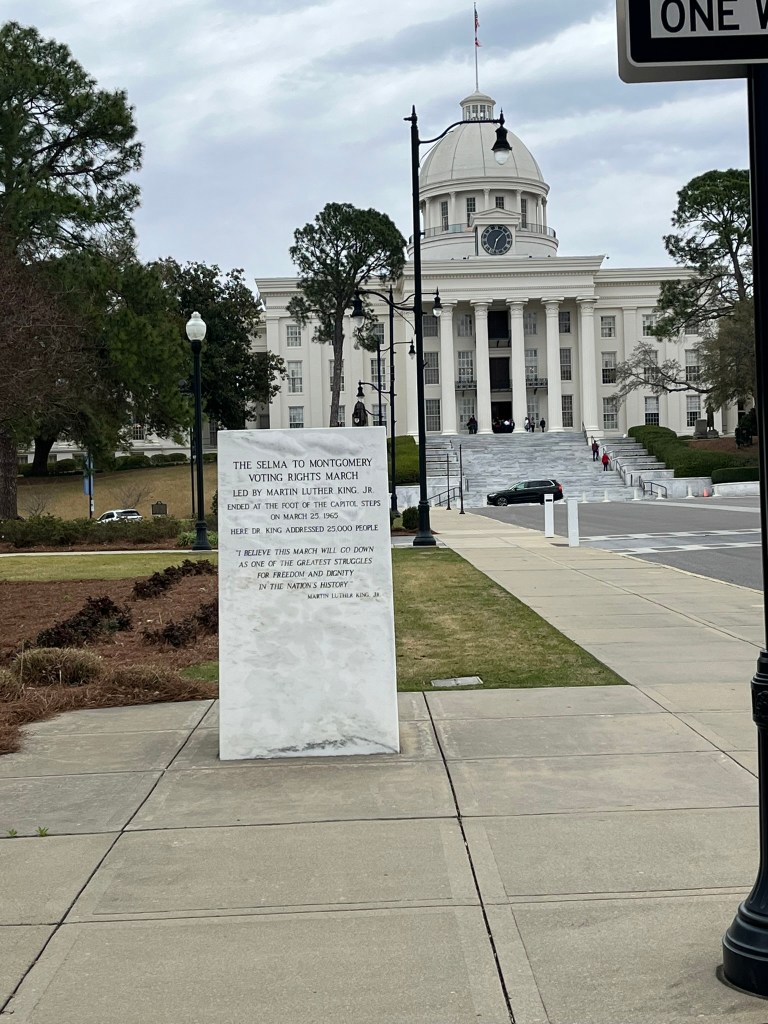

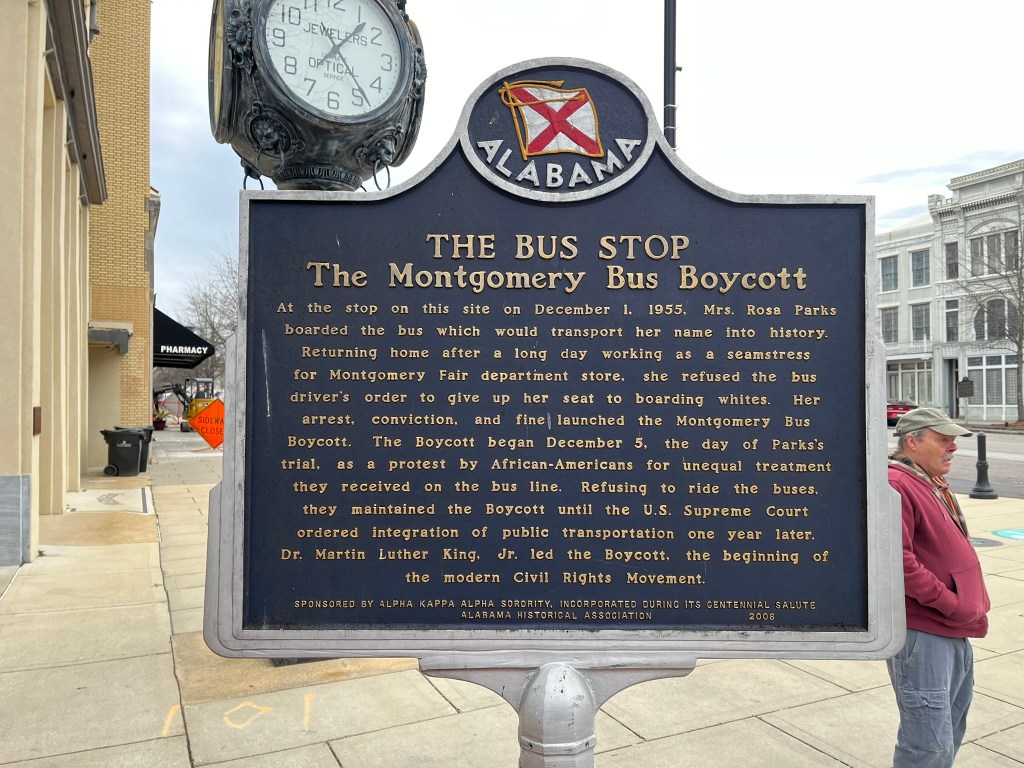

.So arduous was life that many enslaved Africans dreamt of escaping the system and rebelled. One such incident occurred during the later years of the War of 1812. In 1815, British troops took over Cumberland Island and all its plantations, offering freedom to the enslaved by joining British forces or boarding British ships as free persons headed for British colonies. Over 1,500 formerly enslaved people who made it to Cumberland Island from across the Coastal region sought freedom by boarding British ships to Bermuda, Trinidad, and Halifax in Nova Scotia.

There were a number of plantations on the island by the early 1800s, with the largest belonging to Robert Stafford, who enslaved 348 people at its peak. Stafford let his enslaved people earn their own money working for other plantations after their work was done, so many of them saved money. The Union Army took over the island during the Civil War and freed the enslaved people, who promptly left. After the war was over, some came back and bought land on Cumberland Island with their savings.

After the civil war ended, many wealthy northern industrialist families were drawn to the south. They appreciated the warm weather and real estate was dirt cheap. In the 1880s Thomas M. Carnegie, brother of steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, and his wife Lucy bought land on Cumberland for a winter retreat. In 1884, they began building a mansion, called Dungeness, though Carnegie never lived to see its completion. Lucy and their nine children continued to live on the island. The Carnegies built other mansions for the heirs and owned 90 percent of the island. During the Great Depression, the family left the island and left the mansion vacant. It burned in a 1959 fire, believed to have been started by a poacher who had been shot in the leg by a caretaker weeks before. Today, the ruins of the mansion remain on the southern end of the island.

In 1954, some of the members of the Carnegie family invited the National Park Service to the island to assess its suitability as a National Seashore. In 1955, the National Park Service named Cumberland Island as one of the most significant natural areas in the United States and plans got underway to secure it. Plans to create a National Seashore were complicated when, in October 1968, some Carnegie descendants sold three thousand acres of the island to real estate developer Charles Fraser, who had developed part of Hilton Head Island in South Carolina. Other Carnegie heirs (and members of the Candler family who also owned an estate on the Island) were opposed to further development. They joined forces with the Sierra Club and Georgia Conservancy, politicians and activists to push Fraser to sell to the National Park Foundation. They also pushed a bill through U.S. Congress to establish Cumberland Island as a national seashore. This bill was signed by President Richard Nixon on October 23, 1972 and it officially became the Cumberland Island National Seashore.