I had heard of Fred Shuttlesworth, but did not really know what this man accomplished during the civil rights movement until I came to Birmingham, Alabama. We took the Red Clay Fight for Rights tour and watched a PBS Documentary “Shuttlesworth”, both of which I recommend. In order to understand why Fred Shuttlesworth was exactly who the movement needed in Birmingham, one needs to understand what it was like there in the 1950s and 1960s under the rule of Bull Connor.

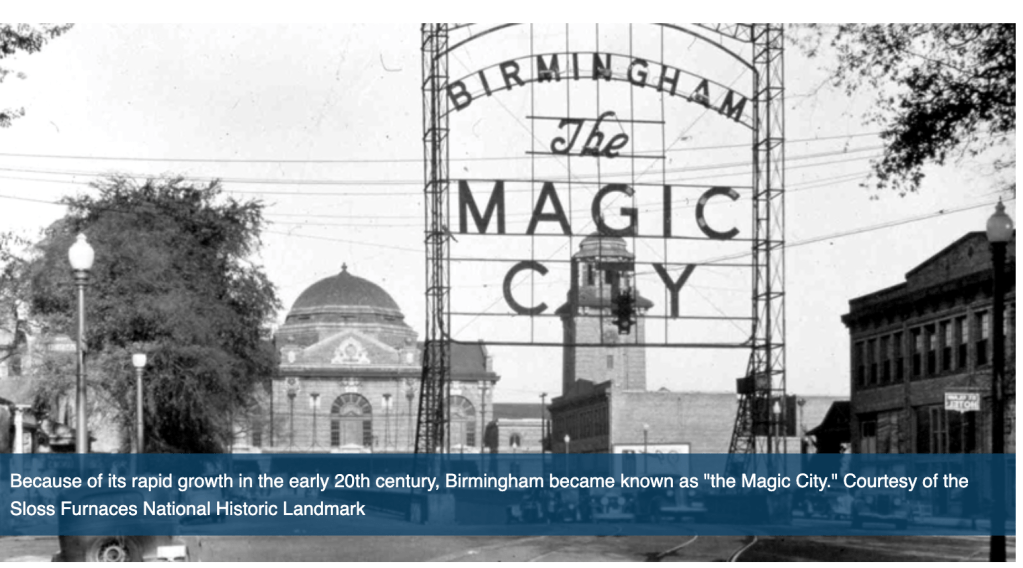

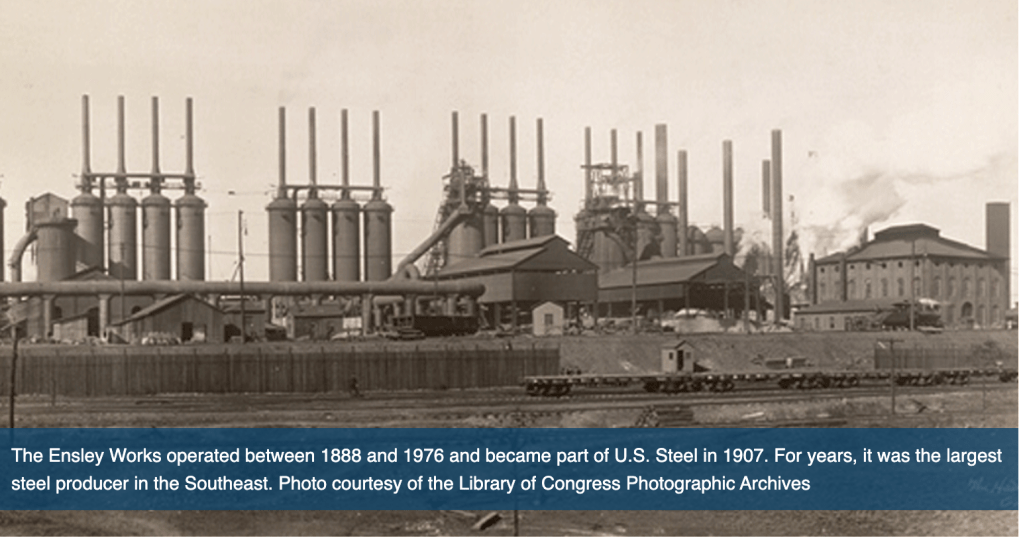

Birmingham was a company town with the owners of the steel, iron and coal companies making the rules. They were segregationists and there was agreement that Blacks should be kept in their place. Birmingham was essentially a police state supporting the industries. Bull Connor became the political intermediary between the corporate interests and the Ku Klux Klan, so that the corporations could keep their hands clean. In the documentary “Shuttlesworth”, eye witnesses talk about the Klan regularly parading with the police cars leading the procession. If a Black person stepped out of line, they could expect a violent reaction- bombing, beating, arrest or even lynching.

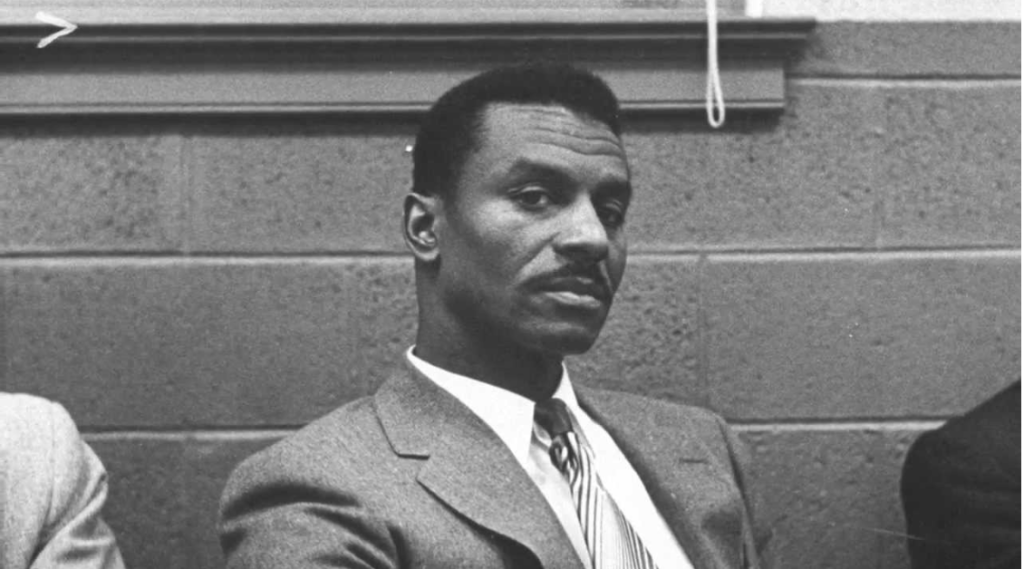

Fred Shuttleworth was described as a warrior, leading people in to battle, willing to risk his life for change. Some folks said he was crazy- they bombed his house, beat him up multiple times, took his car yet he persisted and refused to give up. He was not afraid of Bull Connor; he always believed that God would protect him. He was called “the most courageous civil rights fighter in the South” by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth was a firey preacher with an authoritarian personality. When he was growing up in an abusive household in Montgomery, his mother put him in charge of his 8 younger siblings. He felt like he was being prepared for something and other people felt that too. He learned his persistence from his mother. He knew by the time he was 22 years old that he would be a preacher.

Reverend Shuttlesworth came to Birmingham in 1952 and became preacher of Bethel Baptist Church in 1953. In 1956 the Alabama attorney general outlawed the NAACP, so Reverend Shuttlesworth established the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), serving as president of the group until 1969. The ACMHR coordinated boycotts and sponsored federal lawsuits aimed at ending segregation in Birmingham and the state of Alabama.

The Shuttlesworth family lived next to the church. On Christmas Day, 1956, sixteen sticks of dynamite that had been placed under the house where the bedroom was, exploded and the house collapsed. Fred walked out of the rubble without a scratch on him. Andrew Manis, a member of the church said, “if we had seen Jesus walk on water, we wouldn’t have been any more reverent than we were when we saw Fred come out of that building alive. Fred Shuttlesworth was not only their man but God’s man.” He and his church survived two more bombing.

After the Brown vs.the Board of Education Supreme Court ruling desegregating schools, Birmingham schools stayed segregated. Shuttlesworth tried to enroll his own children at a white high school in Birmingham. The Klan was waiting for him in front of the school and beat him so bad he ended up in the hospital.

Shuttlesworth served as secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) from 1958 to 1970. Joining forces with the Congress On Racial Equality (CORE), Shuttlesworth helped organize the Freedom Rides and in 1963, began a campaign called Project “C” to fight segregation in Birmingham through mass demonstrations and boycotts. Project “C” was about conflict, and they had all of the ingredients to make national headlines in Birmingham. They could count on Bull Connor to create physical conflict, so Shuttlesworth convinced Martin Luther King to come. The strategy was to fill the jails until they overflowed. There were lunch counter sit-ins and some arrests, but the adults were not showing up en mass to be arrested for fear of consequences. This is when the idea of the childrens march was hatched, which was an incredible success. A thousand children showed up to march and over 800 were arrested. The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was where they held the mass meetings and trained the children for the march. When the jails overflowed on the first day, Bull Connor brought out the dogs and fire hoses on the second day. The national press was there to let the world know and the movement got the reaction they needed. Their demands were met, but shortly after that the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing took place and four little girls lost their lives. These events, among others, helped bring about the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. After the passage of the acts, Shuttlesworth continued to focus on issues in Birmingham until he died in 2011 at the age of 89. (https://www.nps.gov/. We need many more people today with the courage, conviction and the mind for strategy of Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth.