When Lawrence, Kansas is mentioned, many people think of the legendary University of Kansas Jayhawks basketball team.

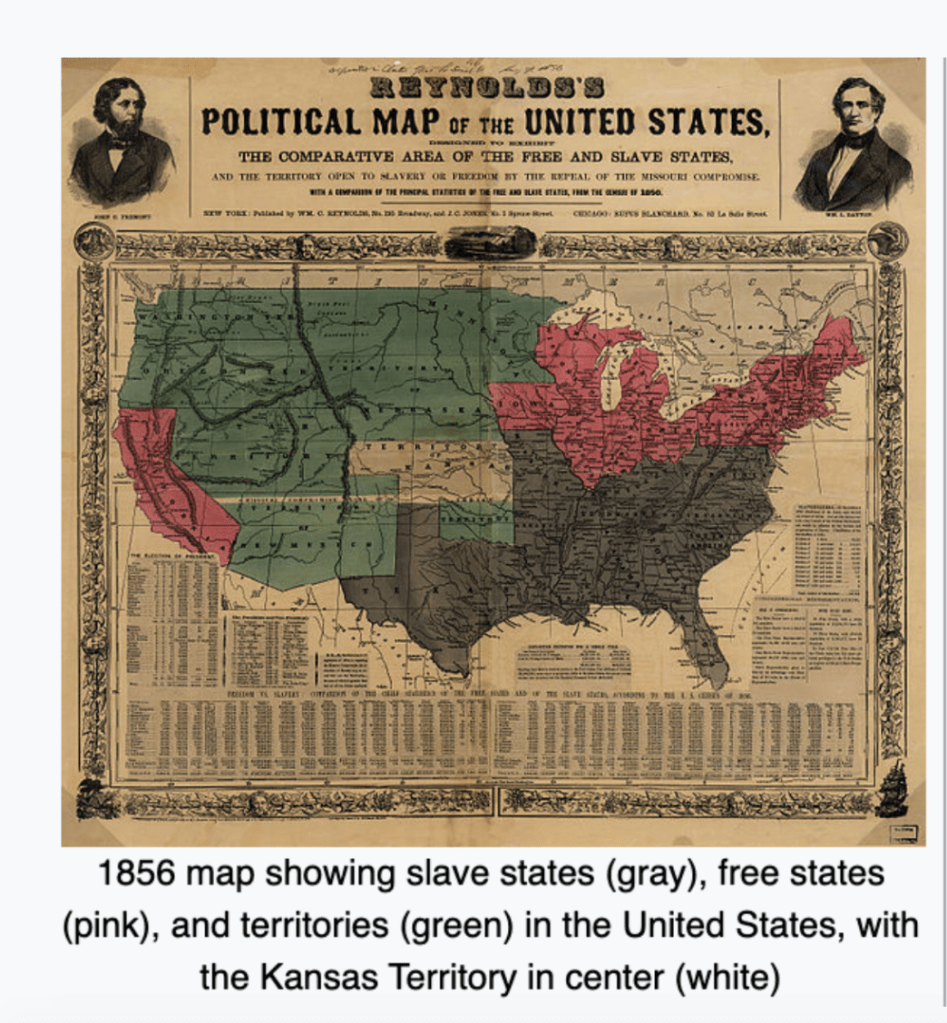

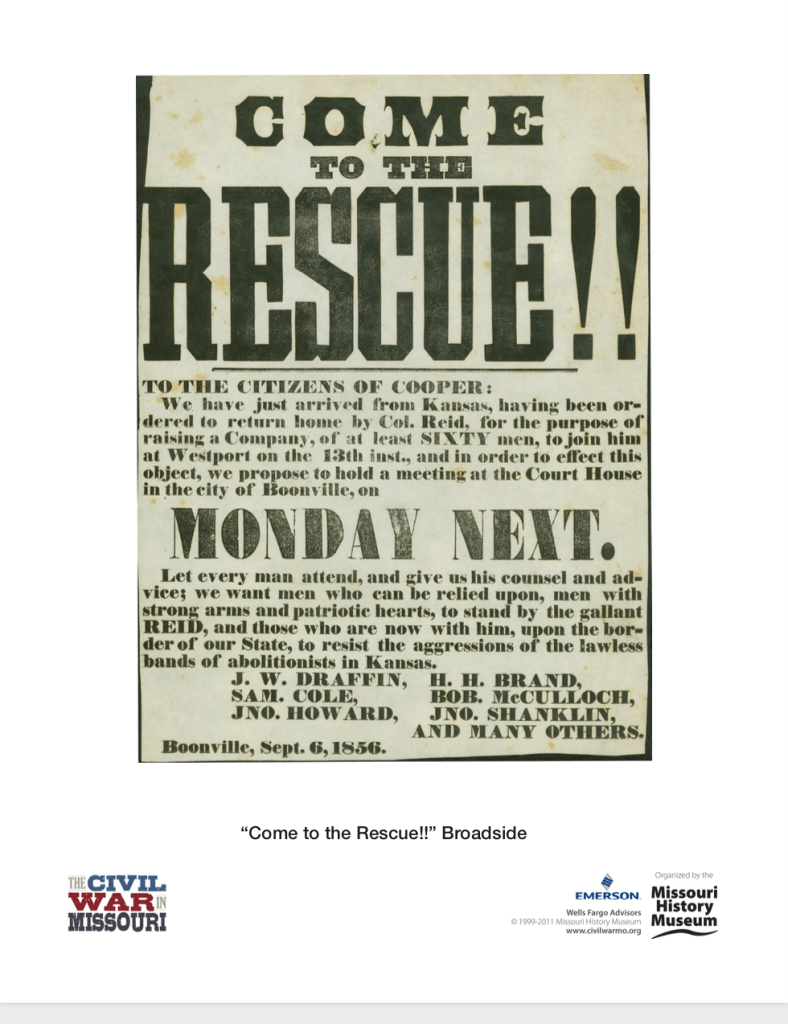

Interesting Fact: “jayhawk” was a term coined during the “bleeding Kansas” period (1854-1861) for militant groups defending Kansas as a state free of slavery. Abolitionist John Brown was a jayhawk. The jayhawks clashed with pro-slavery “border ruffians” who crossed the border from Missouri, a slave state. Lawrence was ground zero for the “bleeding Kansas” clashes leading up to the Civil War. It all started in 1854, with passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, opening Kansas Territory to settlers who would then vote whether to be admitted into the Union as a slave or free state.

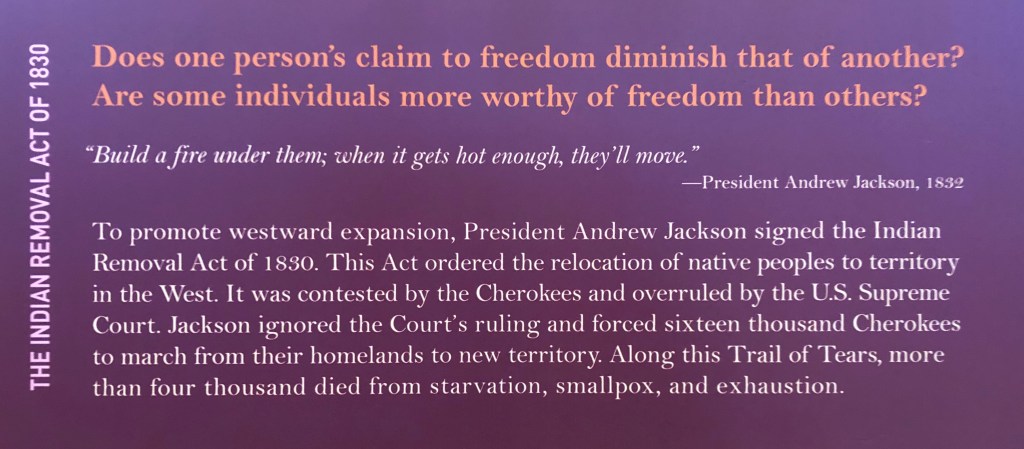

According to the Shawnee Tribe website, before the Kansas Territory was established in 1854, this land was part of the 1.6 million-acre Shawnee Indian Reservation, via a treaty ratified by Congress in 1825. After 1854, the government took much of the reservation and opened it up for white settlement. Brutal abuses by white settlers forced the Kansas Shawnees to relocate again (they were originally from Ohio) to Cherokee Nation in northeastern Oklahoma.

Wikipedia states that: “anger at the Kansas-Nebraska Act, [that could potentially expand slavery], united antislavery forces into a movement committed to stopping the expansion of slavery, ( which eventually was institutionalized as the Republican Party). Many of these individuals decided to “meet the question [of slavery in Kansas] on the terms of the bill itself” by migrating to Kansas, electing antislavery legislators, and eventually banning the practice of slavery altogether.”

Kentucky to fight the jayhawks.

Lawrence was founded by the New England Emigrant Aid Company (NEEAC), and was named for Amos Adams Lawrence, a Republican abolitionist originally from Massachusetts, who was one of a group of investors who offered financial aid and support for anti-slavery settlers from the East coast to move to Kansas. I was interested to know how the NEEAC motivated people to move to the frontier from Massachusetts for the cause. The NEEAC founders were wealthy. They saw this as a business venture as well as fighting for the anti-slavery cause. They focussed on building the infrastructure in Kansas to encourage settlers. The first thing they did was to build steam saws and grist mills in Lawrence, Topeka, Manhattan, Osawatomie, Burlington, Wabaunsee, Atchison, Batcheller (now Milford) and Mapleton to aid settlers in building homes and feeding their families. They arranged for companies to provide transportation for settlers and offered reduced fares. They provided temporary housing in boarding houses while settlers built their homes. Schools and churches were built and practically given to local communities. Libraries and colleges were founded through efforts of individuals connected with the firm. Finally, they established a weekly newspaper in Kansas to communicate with settlers and promote their cause. The company planned to make a profit on its investments by purchasing the land upon which its hotels and mills stood and, when settlement had increased and land values correspondingly elevated, selling to the eventual benefit of the stockholders. The backers of the company hoped to raise $5,000,000 and send 20,000 settlers into Kansas. The plan received wide publicity in the New England newspapers of Horace Greeley, William Cullen Bryant, Thurlow Weed, and others. The company itself issued descriptive pamphlets and its advocates toured New England lecturing on the benefits to be derived. The project was very successful in the beginning, with 1,250 emigrating to Kansas in 1954 (the first year of operation), but interest waned over time. In terms of persons relocated in Kansas, it has been estimated that the company was directly responsible for only about 2,000 of whom perhaps a third returned to the East. Instead of the $5,000,000 it hoped to have, the company actually accumulated only about $190,000. No profit was ever made, but the company did have an impact on the border wars, spurring pro-slavery settlers to move from Missouri and it did help mobilize the political forces necessary to have Kansas vote to enter the Union as a free state in 1961.

It is ironic that the fight for freedom from slavery in Lawrence was at the expense of the Shawnees. Also, that the abolitionists behind the success in Kansas may have been largely motivated by profit and settlers by opportunity rather than politics. As I learn more, I find that the fight for justice is often nuanced and it is not as easy to characterize right from wrong, good from bad as I would like.

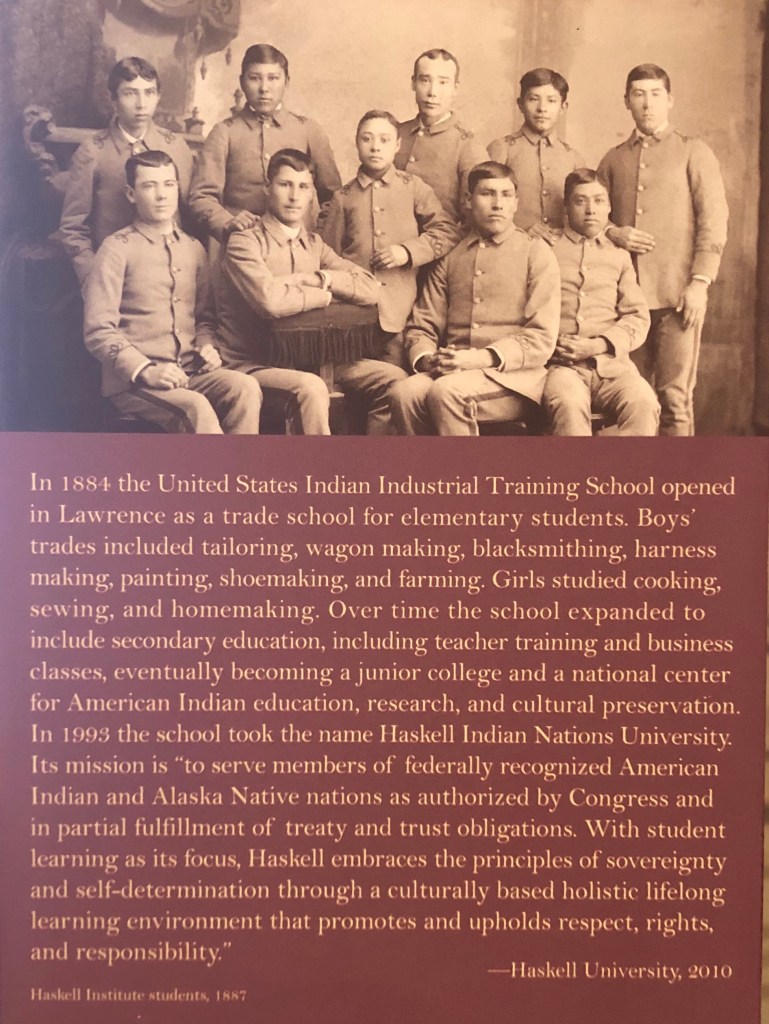

We had never heard of another college in Lawrence – Haskell Indian Nations University. It is a four year college that serves 1000 students per semester representing 140 tribal nations. It was founded in 1884 by the U.S. government as one of 5 Indian Boarding School designed to obliterate their Indian culture. The United States Indian Industrial Training School was year-round; children were not allowed to speak their native languages or sing native songs. When children arrived at the Training School their native clothing was taken away and traded for ‘English clothes’ and their braids were cut off. There are accounts of physical and emotional abuse on the children, especially in the earlier years of operation.

According to the Haskell Indian Nations University Cultural Center website: “The museum celebrates the strength and resiliency of the students and their contribution to what today has grown to become Haskell Indian Nations University. Punctuating the re-emergence of Indigenous expression, Haskell strives to incorporate the elements of Tribal pride and self-determination into its academics and University spirit. Absorbed into the past was an institution founded to kill the Indian and save the child; instead Haskell has victoriously emerged as an opportunity for students to become the change they want to see in Indian Country. Fundamentally through the continued efforts of Haskell students and Alumni the legacy of Haskell continues to live and thrive.”

Carnegie Library Building

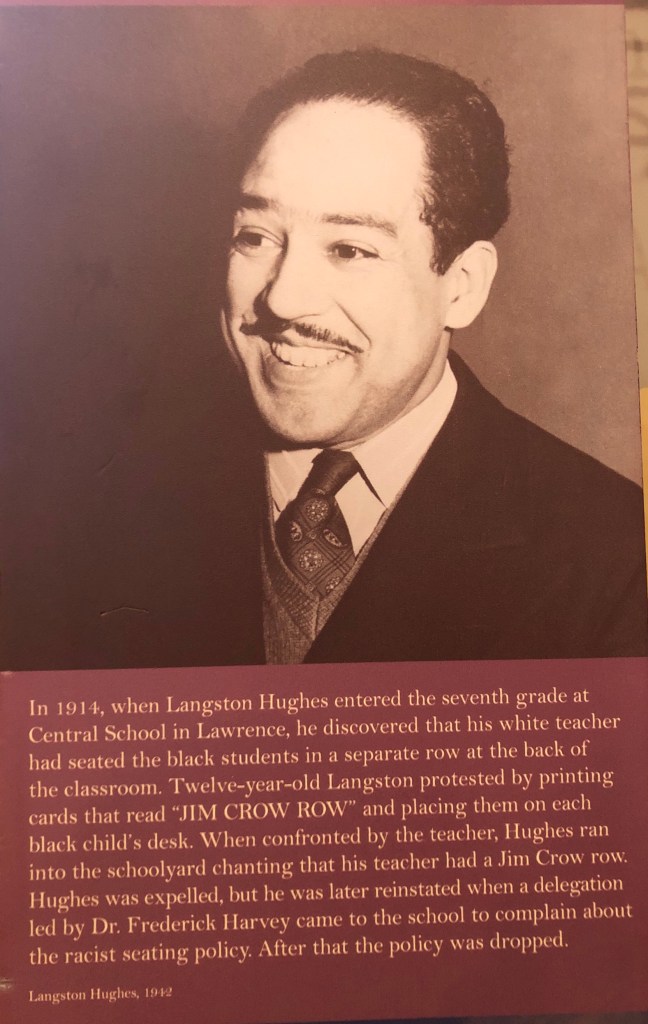

The last interesting thing we learned about Lawrence is that the poet Langston Hughes grew up there. It is sad that a town created by abolitionists had Jim Cow segregation 60 years later.