Yesterday we visited Covert, Michigan, a tiny town of 2,502 people on the shores of Lake Michigan, where there are many parks and most people own their own modest homes. Covert has a unique history. Ever since it’s founding in the 1860’s, the town has been integrated, an anomaly for conservative western Michigan.

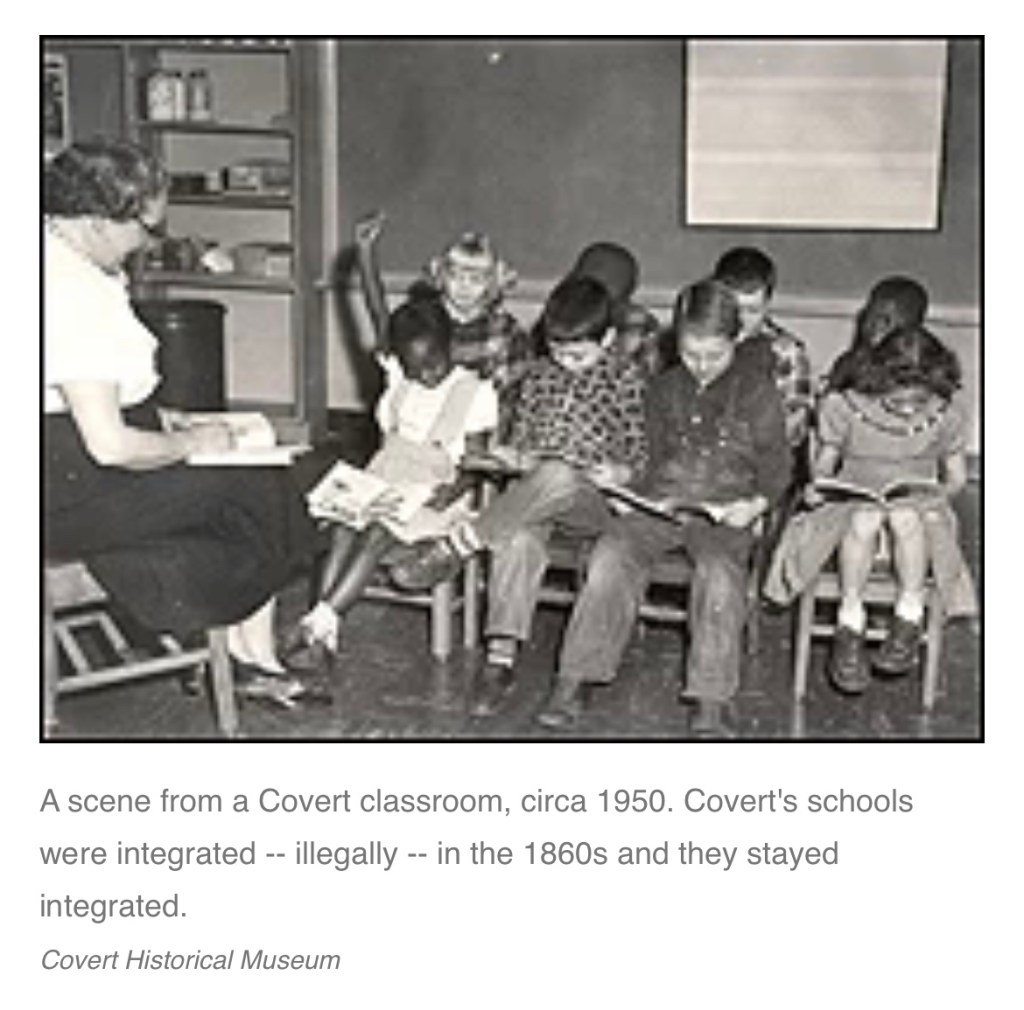

The school had both black and white students starting in the 1860s. Blacks were elected to numerous positions from 1868 on.[4] The Covert cemetery is the final resting place of both black and white Civil War veterans.[5] The town was not formed by abolitionists or as a freed-black settlement; It was just a bunch of New England whites and former slaves who didn’t mind the color of each other’s skin, working together to carve a community out of the Michigan wilderness.

According to the Detroit News article about Covert:

“For 151 years, it has been a land of racial hopes and dreams. Settled by whites and blacks just after the Civil War, it remains the most diverse community in Michigan, according to an analysis of census and demographic data. The different races sat together in one-room schoolhouses in the early 1900s, danced together at sock hops in the 1950s, and were buried side by side at the end of the century, as attested by photos at the Covert Historical Museum. ‘We’ve always looked out for each other,’ said Barbara Rose, 70, a former supervisor who has lived here since 1952. ‘We’ve always come together whenever there’s bad stuff.’”

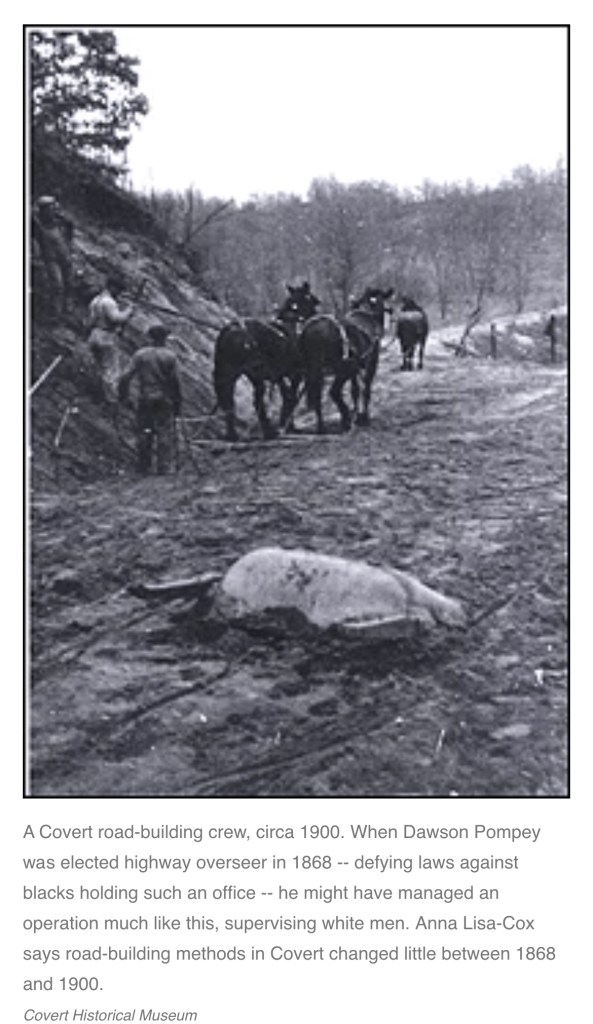

In 1866, these town folk joined together and quietly flaunted racial laws and customs. It was illegal for whites and blacks to attend school together so the township omitted the race of students when sending rolls to Lansing for state aid, said Anna-Lisa Cox, who wrote a book about the town called A Stronger Kinship: One Town’s Extraordinary Story of Hope and Faith . In 1868, the same year Michigan voters rejected the right of blacks to vote, Covert elected Dawson Pompey, a black farmer who was the son of a slave, to supervise the building of roads, Cox said. By the end of the century, the township had elected 29 blacks as township trustees, constables, drain commissioners and election inspectors, and the first black justice of the peace in Michigan.

In recent years, the beliefs of long-time Covert residents are being tested by a large influx of Latinos, who now are 28% of the Covert population.. They came for the fruit farming. This part of Michigan is known as the Michigan’s Fruit Basket, where pears, peaches, apples, apricots are grown. In Covert, it’s blueberries. Many immigrants came from Chicago, drawn to Covert because it feels like their home in rural Mexico. Some have been able to buy small blueberry farms.

At first, the transition was difficult. Tempers flared between Black and Latino students at the high school. Teachers struggled to communicate with Spanish-speaking students. Many town residents were slow to accept the newcomers because they expected them to leave after the growing season like farm workers in the past. But these folks had come to stay.

Gradually the students got used to each other and tensions eased. Maria Gallegos was elected to the school board in 2014 and became president last year. The older folks, who are proud of the town’s legacy, had an easier time of it. “Nobody cares if someone is black or white or Hispanic,” said Jean Robinson, 75, who was born in Covert and is secretary of the museum board. “We don’t look at color.”

Leave a comment